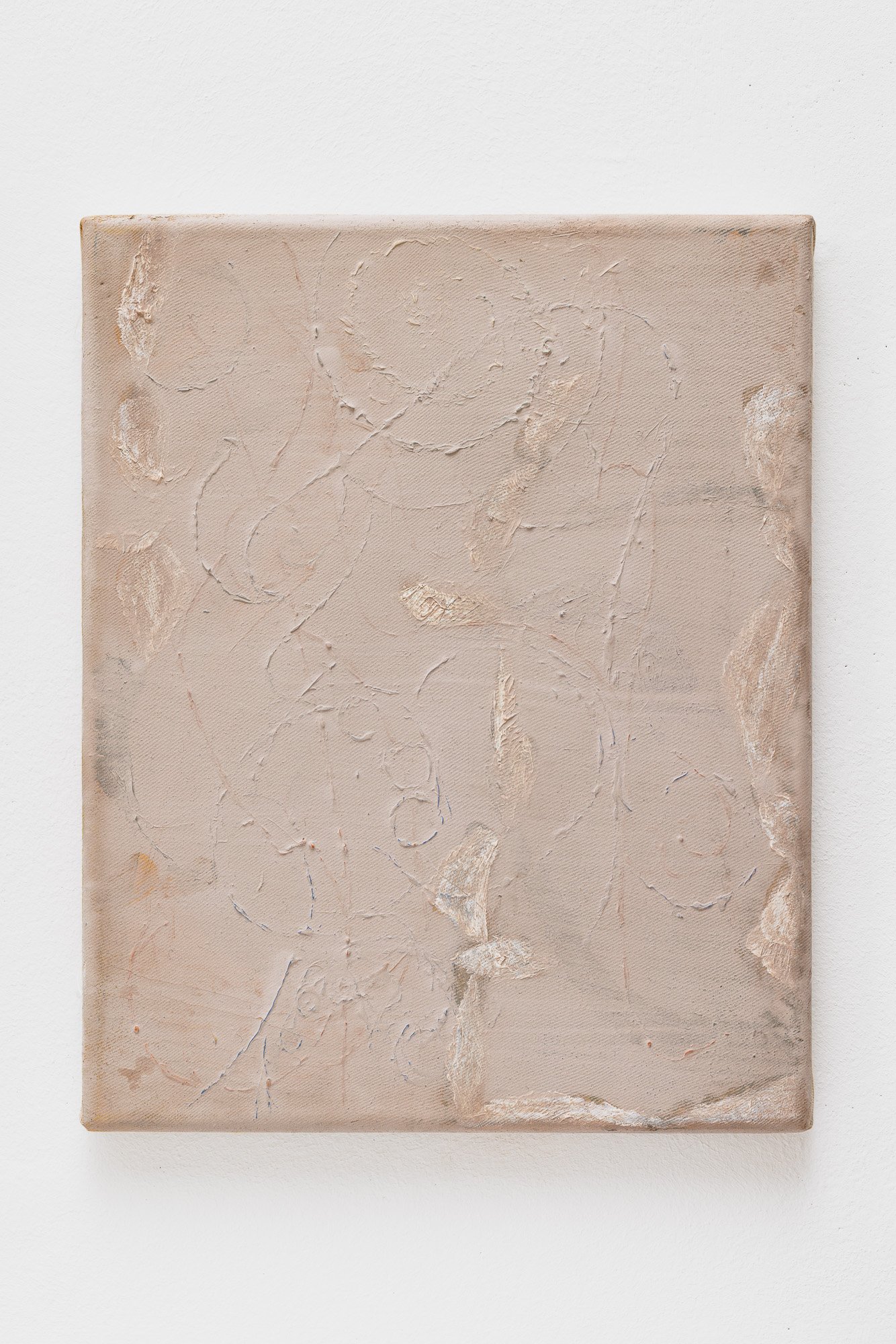

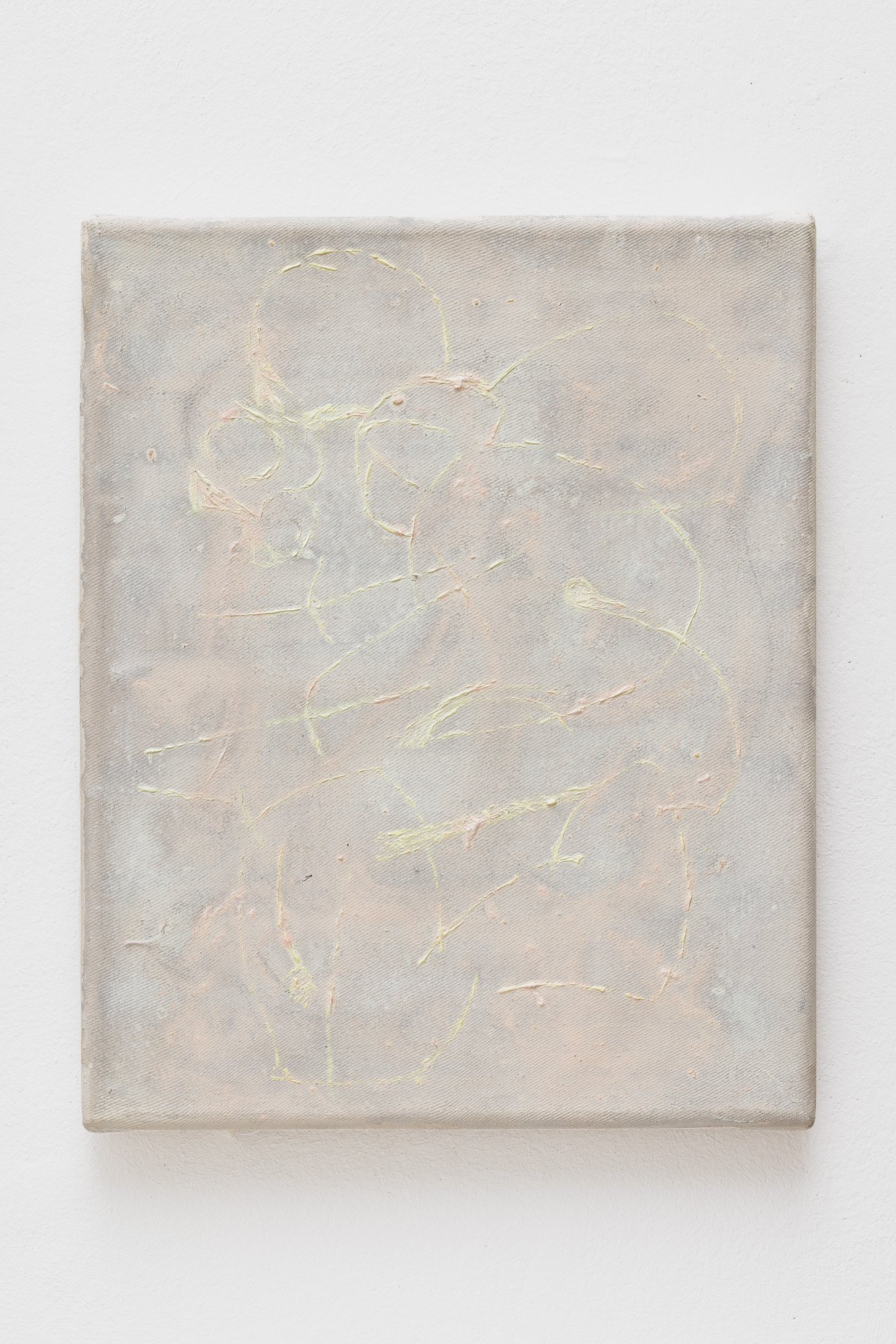

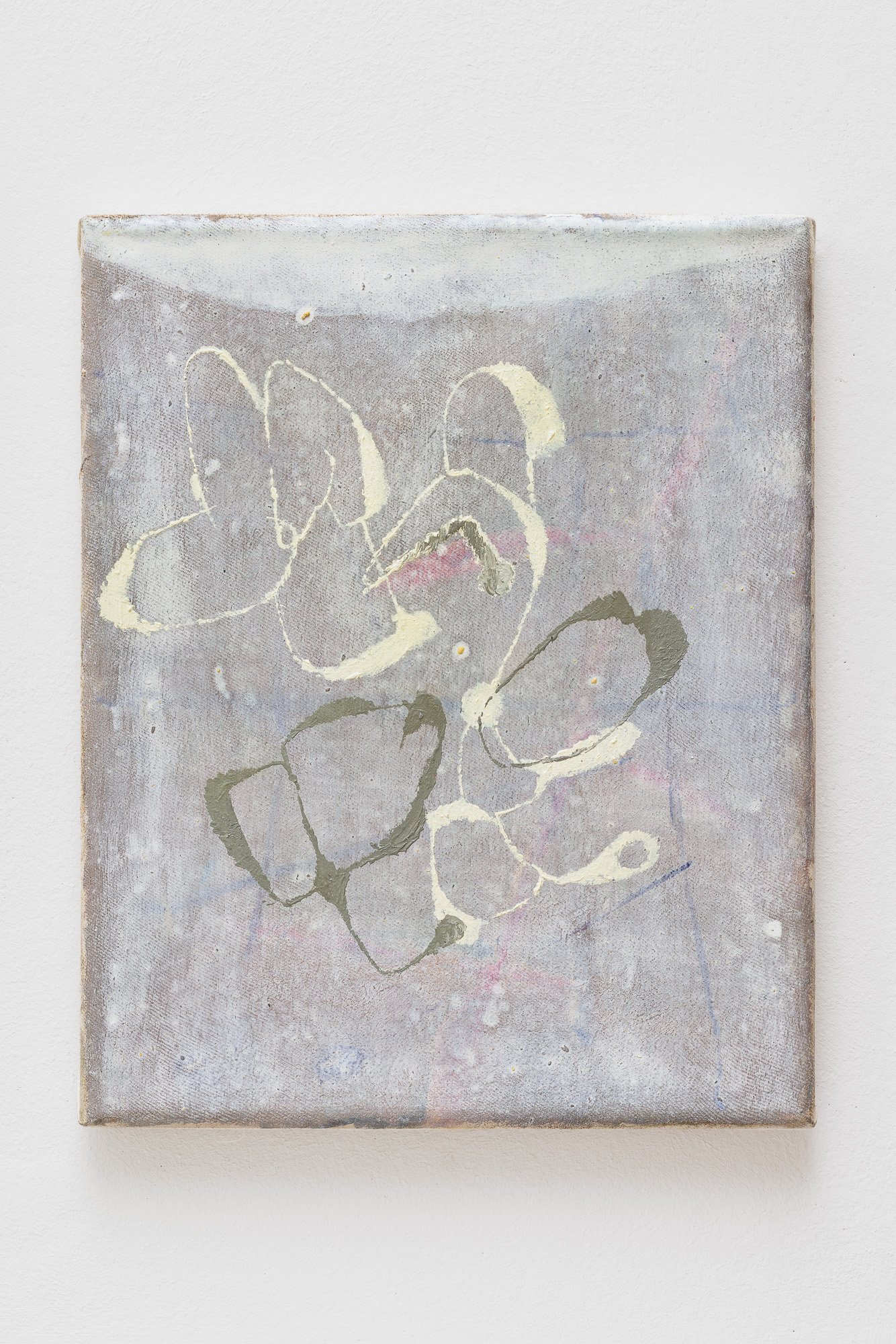

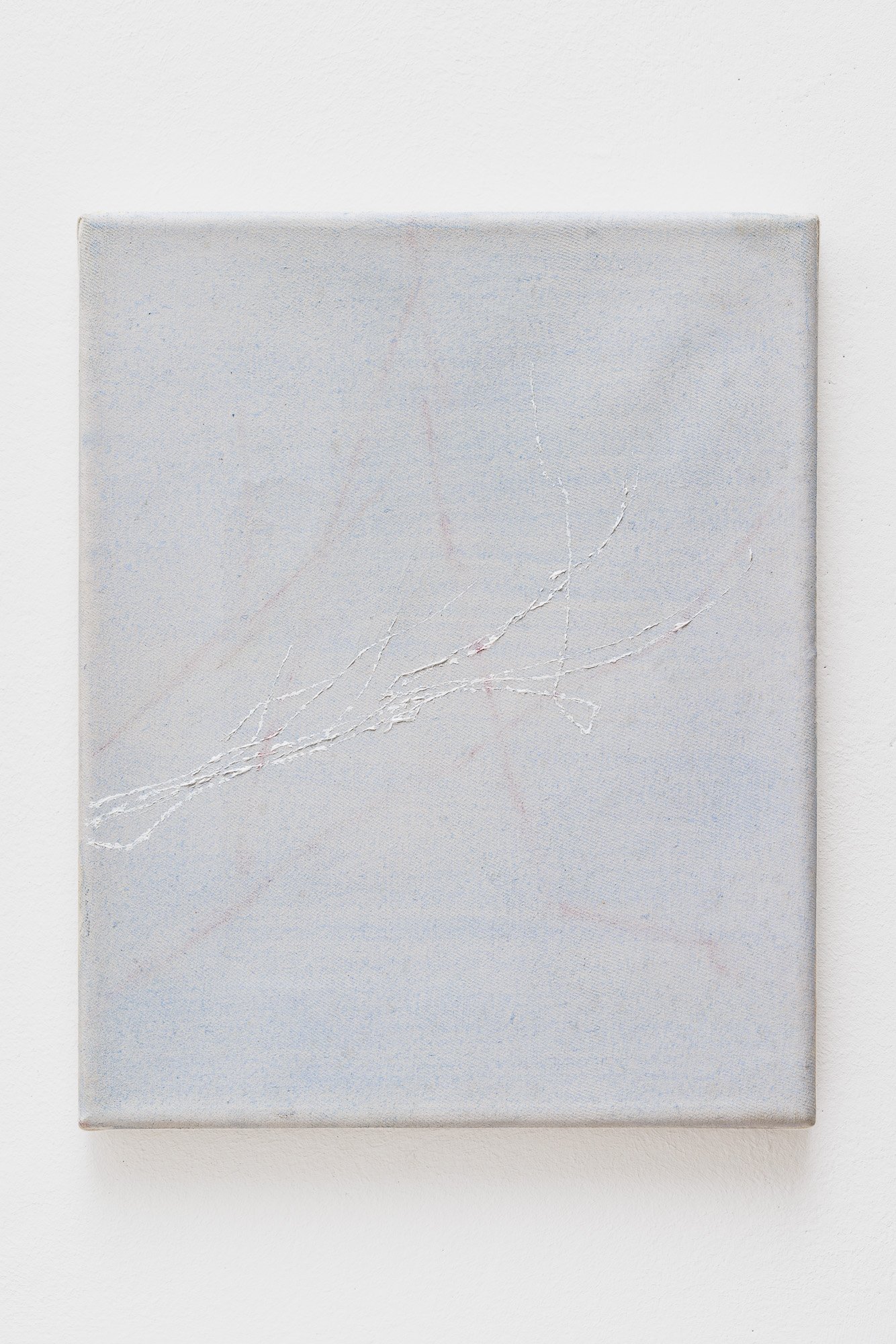

TEGET

Edin Zenun

OCT 18 — NOV 26, 2022

Reflecting on the underlying knowledge of collapse that intertwined with the hedonistic dream of the Weimar Republic, Teget continues Edin Zenun’s inquiry into the historical space between abstraction and figuration. He brings together the short-lived architectural turn of brick expressionism, with its excess of ornamentation and emotion of form, with North American modernist Marsden Hartley, who famously painted his lover, a German officer, by the medals, ribbons and flags of his uniform.

-

Dex closes his eyes and sees a marine blue, quieter than the waves, the sea. Then he’s back in the room that leads straight to the sewage, with wafting steam of recent piss that smells like turmeric as it steeps in the trough with the piss brick.

There’s a screen, high on the wall above Dex’s station, which shows the men working out in the other room. They dance for cardio and pump iron and when they are sufficiently slick with sweat, they walk towards the scraping rooms and are misted with oil for even coverage. Then they are scraped; a metal rod over every bump and ridge of their body. This provokes the need to urinate. Dex kneels at the trough watching for stray oil. It’s more common with the uncut guys because the forceful mist of oil somehow gets under the foreskin, and accumulates. It’s supposed to accumulate - harvesters wait til the end of day to scrape the greasy smegma from under the glans into containers - it sells for a premium. Most of the subjects find it too intense for each scrape, and apprehension changes the quality of the sweat.

Dex and colleagues work beside the harvesters as conservators. They preserve the comforting order of the scraping rooms. Tiled walls, erected with verve into cubicles. But getting gloios - olive oil that’s become a thicker balm after being scraped off sweaty men, mingled with skin and dirt - is not without stringent quality control. It’s a bit like wagyu farming, there’s translatable value in how the animals feel. And much like wagyu farmers massage and feed cattle delicious foods until they are shock-slaughtered, Dex is part of the team that keeps the men comfortable even while they’re scraped into containers for sale as a topical balm or spiritual healing paste. For these special men, Dex is employed to keep the urinals oil-free, discreetly slosh-swiping with a squeegee between uses. Very few men take pleasure in urinating into oily puddles, or into scummy grey bubbles, like sea foam, on the lip of the trough.

Keeping the men happy is paramount; while it’s hard to scientifically prove, the process of emptying a bladder must have some correlation to emptying sweat glands. If their excreted sweat smells like something other than pheromones — or whatever the actual scientific smell for intoxicating masculinity is — then how would that translate for the people who purchase gloios to paint and smear onto their own bodies? How does it translate for these people who are thrilled and dependent on the product’s relationship to its origin.

The men, the producers, are invariably young, the type you’d want to consign to fight for your country even if you were a pacifist, the type who’d be drawn in to the pounding drums of war like they flock for dancing, while wartime remains an unlived abstraction. They are perfect for war because their loss would be a travesty, and because their physical beauty only heightens the pathos of their possible demise. The repercussions of their future actions, curving space.

Dex does not qualify to be one of those men, but he thinks he still looks good. His hair flops, blow-dried, like a young man who videos himself. His confidence comes from his wardrobe. Today, below the knees he wears birkenstocks and calf-high stockings. Erotic in ancient Greco-Roman style, apt since that’s the origin point of gloios. One can also easily tongue out Dex’s foot hair by suckling through the nylon. Moving up the body from there, he wears basketball shorts, then a clingy henley under a corduroy-and-leather waistcoat with corset ties, worn open, which he found with a friend on the street. In the same way that one can compare the devised rarity of club queue to border security, you can compare his look from bottom to top as a bad quote of the historic path of trans-atlantic masculine casual dress. The working class type in sartorial summation. Everything is shrouded, the crack of Dex’s ass the primary wrinkle in the sports mesh as he bends over the urinal. If he stares at his own crotch as he walks past the mirror to the staff bathroom, he can see the shaft move, the soft parts of his torso too. The body is not fantastic, but it’s more than functional.

The actionable hierarchy of men is linked to the desirability of their product to the buyer, but they all dress similarly. There’s a willingness to match. These men who he gently smiles up at while they piss - and knows as actually nice - are largely doing the skinhead thing while out in the world; boots, body, bomber. The hoodie thing is also present. Anodyne codes; to be probably aroused more than disgusted by a military man fantasy, that yummy homophobic forbidden fruit of a sentiment-free orgy in the barracks. Power and rules will always be hot, even if you don’t know the explicit codes. In light of this, Dex doesn’t think his attraction to these men is special, but it’s also not as though he’s actively trying to fuck fascist wannabes.

This product is timely. It is not a fad. Hummus and bacon bits on curly fries; that’s a fad. It makes sense to want to rub skin and sweat, carried by oil onto the skin. Gloios has the emollient feels of being here to stay. The building repurposed as a facility for production was built nearly a century ago. In antiquity Dex’s job would not be of a free man. But he knows the purpose of his work, these small bottles of paste that emerge from this architecture that circulate, becoming smeared skin barriers on the buyers. These smeared paintings speak of men. They will then march around the architecture. Like sewage, exploding like a firework through the system toward the blue sea.